UMass Amherst chemists, electrical engineers use computing facilities at the MGHPCC to identify new variable for material design.

Read this story at UMass Amherst News

AMHERST, Mass. – By one official estimate, American manufacturing, transportation, residential and commercial consumers use only about 40 percent of the energy they draw on, wasting 60 percent. Very often, this wasted energy escapes as heat, or thermal energy, from inefficient technology that fails to harvest that potential power.

Now a team at the University of Massachusetts Amherst led by chemist Dhandapani Venkataraman, “DV,” and electrical engineer Zlatan Aksamija, report this month in Nature Communications on an advance they outline toward more efficient, cheaper, polymer-based harvest of heat energy.

“It will be a surprise to the field,” DV predicts, “it gives us another key variable we can alter to improve the thermo-electric efficiency of polymers. This should make us, and others, look at polymer thermo-electrics in a new light.”

Aksamija explains, “Using polymers to convert thermal energy to electricity by harvesting waste heat has seen an uptick in interest in recent years. Waste heat represents both a problem but also a resource; the more heat your process wastes, the less efficient it is.” Harvesting waste heat is less difficult when there is a local, high-temperature gradient source to work with, he adds, such as a high-grade heat source like a power plant.

Thermo-electric polymers are less efficient at heat harvesting compared to rigid, expensive-to-produce inorganic methods that are nevertheless quite efficient, Aksamija adds, but polymers are worth pursuing because they are cheaper to produce and can be coated on flexible materials – to wrap around a power plant’s exhaust stack, for example.

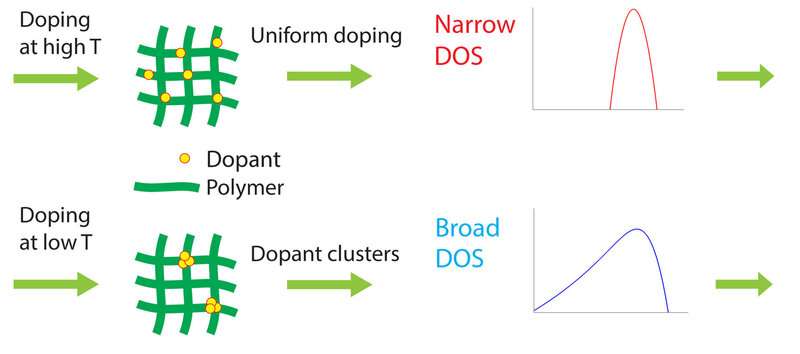

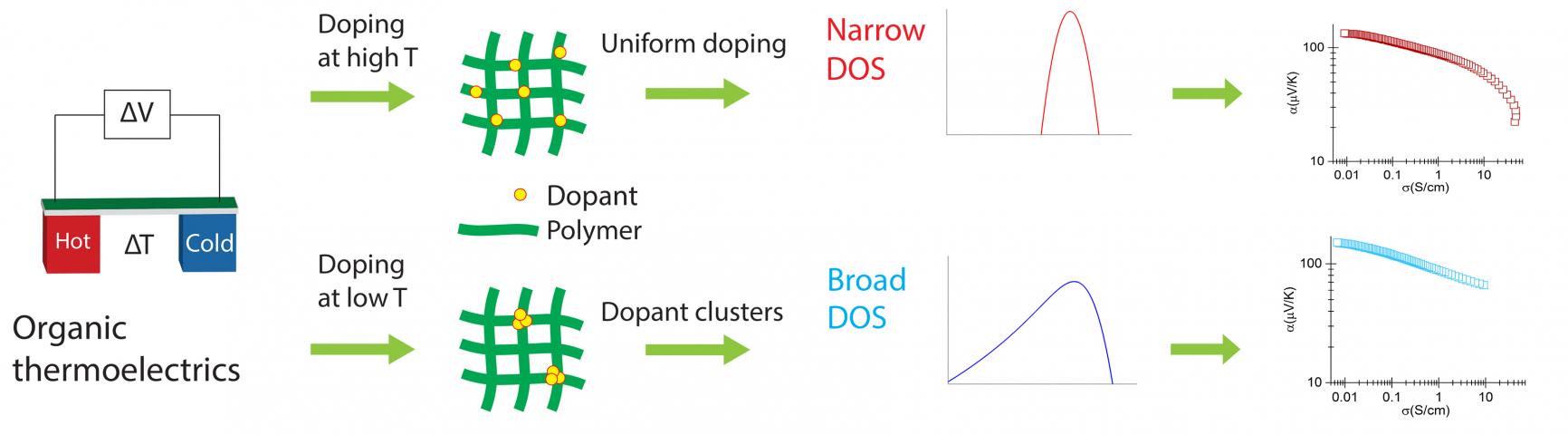

Recently, scientists have been addressing this obstacle with a process called “doping.” With it, researchers mix chemical or other components into polymers to improve their ability to move electric charges and boost efficiency. DV says, “Imagine that we’ve added chocolate chips, a material that improves conductivity, to a cookie. That’s doping.”

But doping involves a tradeoff, Aksamija adds. It can either achieve more current and less thermally-induced voltage, or more voltage and less current, but not both. “If you improve one property, you make the other worse,” he explains, “and it can take a lot of effort to decide the best balance,” or optimal doping.

To address this, DV and his chemistry Ph.D. student Connor Boyle, with Aksamija and his electrical engineering Ph.D. student Meenakshi Upadhyaya worked in what DV calls “a true collaboration,” where each insight from numerical simulations informed the next series of experiments, and vice versa.

The chemists conducted experiments, while the engineering team performed efficiency analyses along the curve from “zero doping” to “maximum doping” to identify the best balance for many different materials. For the massive number of simulations they ran to test hundreds of scenarios, they used the Massachusetts Green High Performance Computing Center in nearby Holyoke.

UMass team of chemists and electrical engineers outline a new way to advance a more efficient, cheaper, polymer-based harvest of heat energy to produce electricity. Graphic courtesy of UMass Amherst/Meenakshi Upadhyaya.

Connor J. Boyle et al. (2019), Tuning charge transport dynamics via clustering of doping in organic semiconductor thin films, Nature Communications, doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10567-5

A Little Bit of This... A Little Bit of That... MGHPCC News